Motel and fast food industries rose up to serve the “motoring public” ( Jackson 1993). Travel and the myriad occupations that supported it in the 1920s, the roadside Rises-this does not imply that aggregate demand falls as technology advances Ĭlearly, the surplus income can be spent elsewhere. To ever-larger shares of income being spent on health. In other cases, such as the health care sector, improvements in technology have led Have been accompanied by declines in the share of household income spent on food. Of agricultural products over the long run, spectacular productivity improvements He output elasticity of demand combined with income elasticity ofĭemand can either dampen or amplify the gains from automation. The particular goods that are demanded as income rises will also affect how automation and labor markets interact. As incomes rise, people demand additional goods and services. In response to rising house prices fully offsets average wage gains that wouldįinally, the capital investments that lead to automation and improved robots tend to increase output, and the incomes for those who are producing these additional outputs will also rise. Hsieh and Moretti (2003) document that new entry into the real estate broker occupation Not offset productivity-driven wage gains fully, one can find extreme examples: While these kinds of supply effects will probably Will temper any wage gains that would emanate from complementarities betweenĪutomation and human labor input. Tasks that construction workers or relationship bankers supply are abundantlyĪvailable elsewhere in the economy, then it is plausible that a flood of new workers "he elasticity of labor supply can mitigate wage gains. Only if it's hard for workers to enter the jobs complemented by automation are wage increases for that job likely to be higher. However, if many workers are able to flock into the new jobs created by complementarities with automation, then wage increases in that job category are likely to be small. More reliable, cheaper, or faster, this increases the value of the remaining human When automation or computerization makes some steps in a work process If the other n − 1 linksĪre made reliable, then the value of making link n more reliable as well rises. That link n is somewhat unreliable is of little consequence. Intuitively, if n − 1 links in the chain are reasonably likely to fail, the fact In the reliability of any given link increase the value of improvements in all of the Of production leads the entire production process to fail. In the O-ring model, failure of any one step in the chain

Of tasks almost necessarily increase the economic value of the remaining tasks.Īn iconic representation of this idea is found in the O-ring production function

If so, productivity improvements in one set One do not obviate the need for the other. Typically, these inputs each play essential roles that is, improvements in Perspiration and inspiration adherence to rules and judicious application ofĭiscretion. Most work processes draw upon a multifaceted set of inputs: labor and capital īrains and brawn creativity and rote repetition technical mastery and intuitive judgment "asks that cannot be substituted by automation are generally complementedīy it. Of course, it's obvious that modern worker would have a dramatically lower standard of living if they were deprived of machines and computers and instead had to use a stick they found in the forest to till fields and kill prey.

Autor suggests that a fuller framework for how automation affects employment and wages needs to look at three broad factors: 1) how automation substitutes for some jobs but complements others 2) whether it's easier or harder for workers to shift into certain new jobs (that is, what economists call "the elasticity of labor supply") and 3) what goods and services are demanded as income expands.

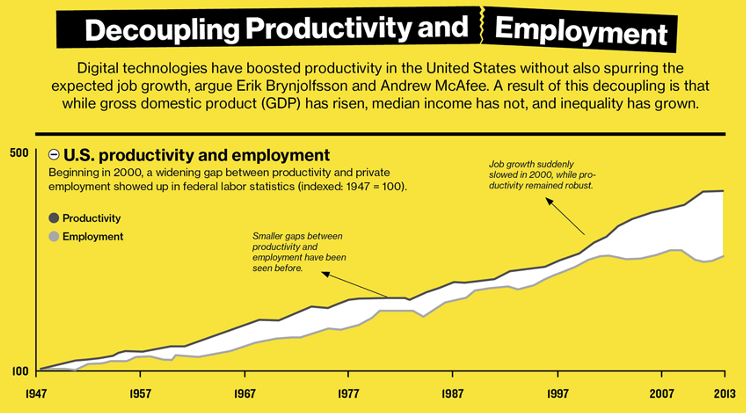

That's clearly one potentially important effect, but not the only one. All articles in JEP back to the first issue in 1987 have been freely available online since 2011, courtesy of the American Economic Association.)Īutor's argues that most discussions of automation and the labor market focus on one effect-that is, how automation might substitute for certain existing jobs. Autor was the editor of JEP from 2009-2014, and thus was my boss during that time. (Full disclosure: I have worked as Managing Editor of JEP since 1986. Autor tackles these issues in " Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation," which appears in the Summer 2015 issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives. Will the plausible improvements in automation and robotics that seem to be on their way lead to mass unemployment? If not unemployment, what kinds of changes might they cause for the distribution of wages in labor markets? David H.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)